Hanko — Japanese Signature Seals

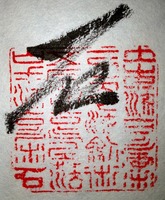

by Steve WeissThere comes a time in the life of an instructor when you are faced with the task of issuing menkyo (rank certificates) to your students. One of the essentials pertaining to this job is the proper use of hanko (seals). The first thing you must do is of course find a qualified seal carver to make the actual seals for you. At this point you will probably wish to have at least three sea...

Read More!Deshi

by Lynn ReafsnyderMost of us have used the word deshi, often without any real understanding of just what the term means. Many of us hearing the word think of the usual, poor translation of “student,” but the word really means something much more. In Japanese, the term for student is gakusei and the term for disciple is deshi. There is a difference.Let’s take a look at the kanji ...

Read More!Lessons from the Gorin no Sho

by Robert WolfeIntroductionThe following article has a very long history. It was originally written in 1977 as a paper for a college course examining Japan from the perspective of cultural anthropology. In 1981, it was accepted for publication in The Bujin, and it became my first writing credit. A reworked version later appeared in the second issue of the Journal of Asian Martial Arts, in 1992. I...

Read More!Conditioning Exercises for the Abdominals

by Robert Wolfe / Illustration by Rosanne Wolfe“The serpent in the stomach.” For centuries, martial arts instructors have used this colorful metaphor to describe the source of muscle power for most traditional techniques.Working in concert, the muscles of the hips and abdominal region produce the torque that drives cuts, strikes, and throws. Most people today train their midsections f...

Read More!Capturing the Absolute Moment

by Okabayashi Shogen It is very hard to express aikijujutsu in words, but I will give it my best effort. I expect that all of you reading this want to become stronger, but have you ever considered exactly how strong is strong enough? Is it enough to be the strongest in your neighborhood? Or would you like to be the strongest in your city or state? Perhaps strongest in the country? &nbs...

Read More!Myths of Self-defense

by Robert WolfeMany people seeking martial arts training cite gaining the ability to defend themselves as their primary motivation, while almost everyone seeking training includes “self-defense” capability somewhere in their list of goals. Persons training long-term typically come to recognize a wide range of benefits far exceeding in everyday utility the value of being able to fight ...

Read More!Reasons to Choose Itten Dojo

Here are a few of the many, excellent reasons to choose Itten Dojo:• You will be a member, not a customer (we do not use contracts).• You will train in authentic, heritage martial arts with fully documented lineages tracing directly to Japan.• You will have regular access to some of the most-accomplished, highest-ranking instructors in the world.• Our dojo is widely recognized...

Read More!Knees, Feet, and Ground — the Critical Interface

The knees are some of the most critical, and also most vulnerable, joints in the human body. Protecting the knees in routine training is a primary requirement for long-term participation in martial arts. Equally important, the things a student should do to protect his or her knees can be a gateway to learning how to optimize the power and effectiveness of a wide variety of techniques, regardless ...

Read More!Self Defense Law and the Martial Artist

by Vigiles UrbaniIntroductionAnthony Ervin was a career criminal. He was arrested eight times on assorted robbery, weapons, and assault charges between 1987 and 1996. On October 8, 1996, he accosted Courtney Beswick, a blind man who must have seemed like an easy target. After Ervin’s demands for money were repeatedly refused, he attacked Beswick. Beswick, a long-time practitioner of martial...

Read More!The Last Bugeisha

by Peter HobartWith due respect to Robert Fulghum, almost everything I know, I learned as a bartender: • Welcome everyone through the door, but be ready to show it to them again if need be. • Treat a pauper like a princess, and a princess like a pauper. • There isn’t much that men (and women) of good f...

Read More!No Toy Swordsmen (or Swordswomen)

“Toy swords make toy swordsmen” was an oft-heard litany in the style of swordsmanship we trained in for many years, over the course of two separate periods of time. For simplicity, I’ll refer to this former study of swordsmanship as the “legacy style.” The “toy swords” phrase was intentionally disparaging of anyone training with an iaito (an alloy-bladed,...

Read More!Judo Study Group

Judo is both a martial art and an Olympic sport. The complete art employs throwing, grappling, joint locking and strangling skills. Self-defense applications of the techniques, along with some strikes and blocks, are included at advanced levels. The spiritual discipline aspect of the original judo is generally lacking in the sport version, although few martial arts can compare with either way of ...

Read More!Why Iaido and Jujutsu?

Readers of my book, A Journey of Sword and Spirit, will recognize the derivation of this topic. An earlier version of my essay “Why Iaido?” was published in Bugeisha Traditional Martial Artist magazine in April 2022 and in my book. “Why Nihon Jujutsu?” was published in the August 2023 issue of our dojo journal, and later in my book. These essays described our int...

Read More!Kyudo is Coming to Itten Dojo

Kyudo, the traditional Japanese art of archery, is a meditative and disciplined practice that blends physical skill, mental focus, and spiritual refinement. Known as “the way of the bow,” kyudo is more than just hitting a target; it is a path toward self-improvement and harmony. Practitioners, or kyudo-ka, aim to achieve a state of shin-zen-bi—truth, goodness, and beauty&md...

Read More!